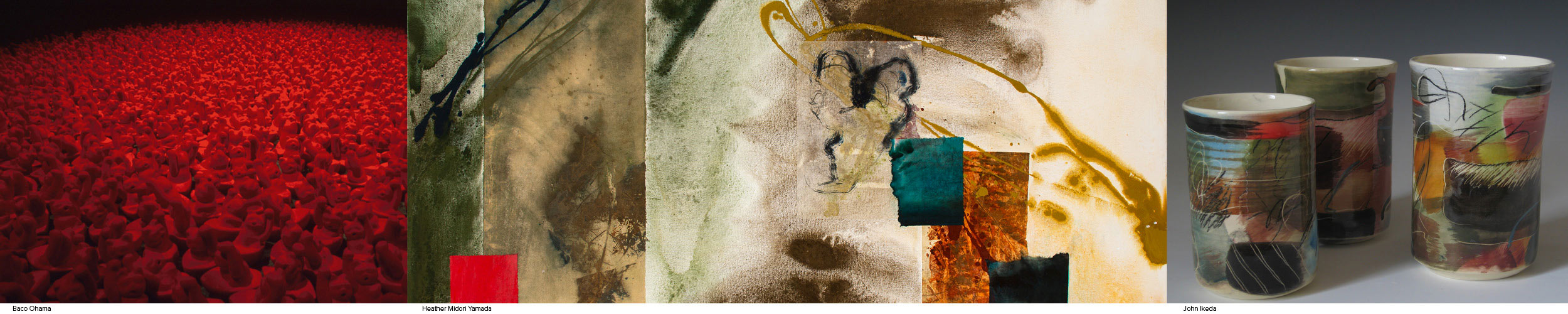

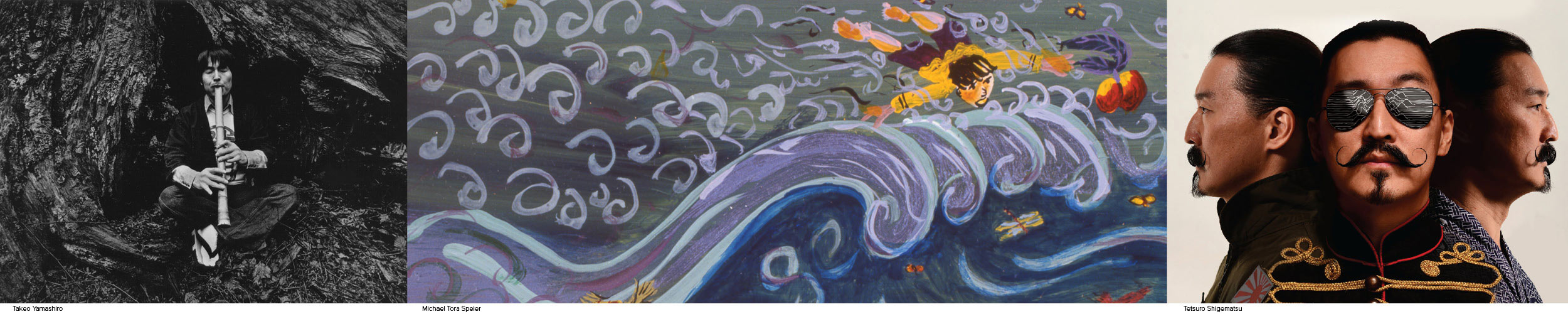

Japanese Canadian Artists Directory

Welcome to the online Japanese Canadian Artist Directory. This directory site has been built on the foundation of a former print directory, Japanese Canadians in the Arts: A Directory of Professionals compiled and edited by Aiko Suzuki in 1994 and its accompanying document, A Resource Guide to Japanese Canadian Culture. This digital iteration includes, and expands on the original. It enshrines the legacy of Japanese Canadian artists whose creative works may not be known, either because they were made prior to the internet era, or have been lost to time. At the same time, the site will allow current, practicing artists an opportunity to connect with peers and discover other artists’ work.The site is navigable in several ways. Artists and artist groups appears as pages under the main discipline categories of Performing Arts, Visual Arts, Media Arts, Literary Arts, Craft, and Traditional Arts. Artists are also classified by region, and by tags which are sub-categories of their main discipline of practice. A keyword search will bring up any artist or artist page (thumbnail) who mentions the word in their bio. For deceased artists, a standard bio is provided along with a generational tag (Issei, Nisei, Sansei, Shin-ijusha) roughly corresponding to the period the deceased artist was living and practicing his/her art form.This site will continue to evolve and grow, allowing new artists to contribute their names as well as allowing researchers and activists to contribute names of artists from the past. This version of the online directory is the work of the Powell Street Festival Society, the Toronto Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre and the National Association of Japanese Canadians. The Powell Street Festival Society will maintain the site and encourages self-identifying artists to submit their information after registering HERE.

» show more

Why a directory based on ethnicity, and why particularly one on Japanese Canadians, one might ask. The story of Japanese Canadians in this country is one of loss, estrangement and reconnection. Intrepid immigrants from Japan (known as the Issei generation) came to Canada with the hopes of starting new lives in communities centered on the west coast. Working in the resource industries of the time – fishing, logging, farming – they flourished and prospered, forming substantial communities throughout the west coast. The children of these Issei, the Nisei, grew up on farms or small logging communities or in segregated city neighborhoods like Powell Street in Vancouver. Then came the Pacific War. After Canada declared war on Japan, racist sentiment against Japanese Canadians reached a boiling point, and the government caved to public pressure to introduce drastic discriminatory policies against its own citizens. 22, 000 Japanese Canadians were dispossessed of their homes and livelihoods, and were forcibly removed from their homes and sent either to internment camps in interior British Columbia or to the sugar beet fields of Alberta or Manitoba. Subsequent post-war resettlement from the camps, either east of the Rockies or exile to Japan, meant that many Japanese Canadians found themselves dispersed across the land living among strangers and having to begin their lives all over again. In particular, the Nisei were badly affected – not only did they experience the shame and stigma of the dispossession experience, they were also burdened with rebuilding the lives their parents had worked so hard to achieve. Into this milieu, was born the third generation – the Sansei – who grew up ‘protected’ from the secrets of this loss of identity and community, until they began asking questions. This questioning led eventually to political activism and a cultural renaissance inspired by the search for an identity, namely a Japanese Canadian identity. The Sansei generation also grew up alongside a new wave of Japanese immigration that occurred in the seventies, allowing for an interesting interchange and exchange of cultural values and ideas. These Shin-ijusha, as they were called and their children, have since contributed greatly to the arts in Canada as their presence in this directory will substantiate. Throughout the generations, and increasingly more so, inter-racial unions created another generation of Japanese Canadians known colloquially as Hapa or mixed-race. Some of these Hapa are Sansei, many more are Yonsei or Gosei. Their unique position in the Japanese Canadian community has also resulted in significant contributions in the arts.

These generational categories of Japanese Canadians are broad, but they provide a purview over time of the perspective of each generation’s experience of life in this country.

In addition to this history, the Japanese culture that has contributed and continues to shape Japanese Canadian identity today is artistically rich in tradition and sophistication. Many art forms practiced in Canada today will have unique counterparts in traditional Japanese culture, for example, in theatre, kabuki or Noh; in dance – butoh and odori; in painting – sumi-e; in craft – ceramics and textiles; in literature, the haiku and tanka, in architecture and design – minimalism and landscaping aesthetics, in music – taiko and shakuhachi – not to mention those other art forms that are particular to Japan like flower arrangement (ikebana,) the tea ceremony (sado), and calligraphy (shodo.)

This is not to say that all Japanese Canadian artists draw on these traditional influences, and some in fact, might be willing to go so far as to say they have rebelled against them or are completely indifferent to them; however, the fact of their existence is foundational. Early Issei poets learned to negotiate the harshness of the Canadian landscape in haiku just as later visual artists learned to see it with the conceptual framework of a Zen-infused sensibility. And not only have Japanese Canadians been influenced by these foundational Japanese precedents but so too have many other Canadians who have learned or studied the traditional arts alongside ‘masters’ who have immigrated here eager to share their knowledge and skill. The old print directory acknowledged these non-Japanese Canadian artists, and this directory will continue to do so in its current form.

» show less

FEATURED ARTIST

The New Canadian’s poetic spirit

In 1943, British Columbia MLA Mrs. F.J. Rolston called Japanese Canadians “unimaginative, unromantic and steeped in a cult of deceit” in an address to the Port Arthur Women’s Canadian Club in Ontario. Commenting on this in The New Canadian, columnist K.W. lamented: “We’ve been so many things before, it doesn’t faze us a bit. But “unromantic, unimaginative”! Mrs. Rolston, you cut us to the quick!”[1].

[1]The New Canadian “Mountain Hermitage” November 13, 1943, page 1.

» show more

Already treated as enemy aliens, banished from their homes, and effectively condemned as saboteurs by their own government when the reason for their forced removal was given as “national security”, by late 1943 the writers and editors of The New Canadian did not bat an eye at the accusation that they were “steeped in a cult of deceit”. But to call Japanese Canadians, and particularly the idealistic young Nisei who had founded The New Canadian, unimaginative or unromantic, must have appeared not only novel, but downright strange. As evidence to the contrary, KW cites “a few lines of verse a small Nisei student group once framed on the wall”, entitled “Higher Education”:

Let them forget their Euclid, Donne and Kant,

If, in long years to come they hear and see,

And call at need,

A wise man’s quiet voice,

A marble arch,

A line of poetry[1].

The New Canadian newspaper was first printed in 1938 with two issues, and began publishing regularly in February 1939. The purpose of the newspaper was to be a “voice” for “the second generation”; that is, for the young Canadians born to Japanese parents who were just coming of age at the time. The declared purpose of the newspaper was primarily a political one: to provide “some medium through which the Nisei might speak his thought and his hopes to the Canadian public at large” in the face of rising anti-Japanese discrimination and to “rally a wavering minority group to a firmer consciousness of its peculiar position and the goal to which it must proceed in the land of its adoption”[2]. However, arts and culture also played an important role in The New Canadian from the beginning. The column “Odds and Ends” in the February 1, 1939 issue includes several poems, both previously published and originals from the author(s), pen named “Deborah and I”, and closes with an invitation to “send me some of your own poetry”[3]. Several readers evidently took up this invitation, as The New Canadian frequently published both longer and shorter poems by a number of authors. Though they were often only credited with initials such as “M.M.M” or “E.H.”, or pen names such as “Dana” or “Asagao”, some contributors, particularly Miyo Ishiwata, gained particular popularity with readers.

There are two clear reasons for The New Canadian’s poetic tastes: the first is simply the inclinations of the editorial staff and contributors. The New Canadian’s first editor-in-chief, Shinobu Higashi, was the first Japanese Canadian to enroll in the English Honours program at UBC, graduating in 1937[4]. Although Higashi left the paper in the spring of 1939, the staff and contributors continued to show an enthusiasm for literature: not only poetry, but discussing contemporary writers such as John Steinbeck and William Saroyan, and speculating on the plot and eventual author of the “Nisei Novel”. Eiko Henmi, another UBC English Honours graduate who would later join the editorial staff, wrote in 1939, “The great Canadian novel is as yet unwritten. Sugita, O Haru, Mark, Mariko – these people are in search of an author. This is an opportunity for someone to weave a tale shot with sunlight and shadow – to write a story significant of that stratum of society who are strangers, and yet not strangers, upon the Pacific coast. Why cannot that someone be you?”[5]. Indeed, many writers and contributors for The New Canadian were members of the “Scribblers’ Circle”, an informal group for “aspiring Nisei writers and embryonic poets and poetesses”[6] which met in Vancouver in 1940-1941. Usually hosted by Muriel Kitagawa, a frequent columnist for the paper, other New Canadian staff and contributors known to have attended include EikoHenmi, Miyo Ishiwata, Mark Toyama, Roy Ito, and the editor-in-chief himself, Thomas Shoyama.

The second reason for The New Canadian’s support of poetry is more ideological.The New Canadian believed that “Cultural, economic, and political assimilation are mutually inter-dependent and any advance which the Nisei make in the one, will aid their advance in any of the other two”[7]. Since The New Canadian’s vision for the Nisei was based on political assimilation (ie. equal citizenship rights, namely the same right to vote, as white Canadians) and economic assimilation (ie. equal job opportunities to enter all professions), it then follows quite naturally that they also encouraged cultural assimilation by publicly celebrating Nisei achievements in western art forms including music, theatre, and literature.

Another example of politicized support for Nisei literature is the Japanese Canadian Citizens’ League (JCCL)’s Short Story Contest, announced in The New Canadian in the fall of 1940. While The New Canadian denied critiques it was an organ for the JCCL, rather than for all Nisei, many of the newspaper’s staff sat on the executive of the JCCL or were closely associated with its leaders: for example, business manager Yoshimitsu Higashi was in National JCCL president Harry Naganobu’s wedding party[8]. The JCCL, an organization which like The New Canadian declared Nisei loyalty to Canada and lobbied for the franchise, also shared its respect for literature. In 1940, they replaced their annual essay contest with a short story contest, in the belief that “dramatic presentation of the stir of human emotion is often more effective and convincing than the most logical and reasonable analysis”[9]. Certainly this was true formany readers of The New Canadian, both Japanese Canadian and otherwise. Watson Kirkconnell, reviewing poetry appearing in The New Canadian during its first full year of publication for “Canadian Literature Today”, felt that he was viewing “an invaluable record of the character and experience of diverse peoples…To read it is to see our newer citizens, not as mute coolies brought in to build our railways and toil in our mines, but as human beings as sensitive as ourselves to all the fundamental emotions and experiences of life”[10]. In essence, this was the core of what the writers and editors of The New Canadian desired..

A more in-depth investigation of poetry and literature in The New Canadian would doubtless yield many fascinating conclusions. For example, the poetry published in The New Canadian as a response to the political climate, often as uncredited space fillers, deserves further analysis. And duringsome of the darkest and most pivotal times in the 1942 period of forced uprooting from the coast,The New Canadian on multiple occasions published inspirational excerpts from established poets of the English canon such as Robert Browning. Columnists would occasionally express their sentiments in verse, often humorously, and on one occasion in 1942 an editorial took the form of a poem, satirizing “That Latest Story You Heard”[11].Close readings of poems and stories by Nisei contributors such as Muriel Kitagawa and Mark Toyama could also reveal much about the writers’ understanding of their emerging identity as Japanese Canadians.

And while I have only looked at a few appearances of poetry and references to literature in the early years of the newspaper, the practice of publishing poetry in The New Canadian continued for many years after the war: Helen Koyama, who worked for the newspaper one summer in Toronto in the 1970s, recalls that “Over the years I would occasionally submit poetry which [editor KC Tsumura] used to fill in blank spaces”[12]. It is a tradition, then, which carried on for decades in the Japanese Canadian community, and survived its greatest period of upheaval with minimal interruption. It may seem like a modest habit, but by making and utilizing precious print space for young Japanese Canadian poets, The New Canadian was most likely the first English-language publisher for Japanese Canadian literary writers, and as such played an essential role in the founding of Japanese Canadian literary expression.

[1] Ibid.

[2] NC “Editorial” Feb 1 1939, page 1.

[3]NC Feb 1 1939, page 5.

[4] Ito, Roy. Stories of My People. Hamilton: Promark Printing, 1994. pp 184-185.

[5] NC “Romance in Vancouver” May 27 1939, page 13.

[6] NC “Town Topics” Jul 24 1940, page 4.

[7] NC editorial “Music Hath Charms” May 1 1939, page 2.

[8]NC “Town Topics” Apr 11 1941, page 4.

[9] NC “Writers Wanted in Short Story Contest” Oct 2 1940, page 4.

[10]Reprinted in NC as “New Canadian Poetry” Dec 22 1939, page 2.

[11]NC April 2 1942, page 2.

[12]Email with the author, June 25, 2017.

» show less