Human life – indeed all life – is poetry. It’s we who live it, unconsciously, day by day, like scenes in a play, yet in its inviolable wholeness, it lives us, it composes us. This is something far different from the old cliche “Turn your life into a work of art”; we are works of art – but we are not the artist.

–Lou Andreas-Salome, psycho-analyst (1861-1937)

Japan

Japan

if I say it enough

do you think it’ll come true?

– David Kenji Fujino, artist (1945-2017)

In 1994, a Japanese Canadian artist directory was published largely through the efforts and leadership of artist Aiko Suzuki. Its official title was Japanese Canadians in the Arts: A Directory of Professionals; in Japanese Nikkei Kanada-jin: Geijutsuka Jinmeiroku. The cover was austere, using the colors grey, white, red, and black. The font used was ‘Century Gothic’ style, done in all caps, with the first letter of each word in red and the following letters in white. The Japanese title, done in kanji, except for the katakana – Kanada – was done in black. Lotus Miyashita was the designer of the book, and its cover reflects in color, tone, and style something of the nature of its contents. Red and white are the colors of the Canadian flag and Japan’s. Black and white are the colors of certainty – dogma, if you will – and grey, well, that is the color representing the state of in-between or neither-nor or both.

Roughly 190 artists appear in that original directory which meant they agreed to put themselves between those covers, bound with others in artistic disciplines vastly different or very similar to their own. I was one of those artists, eager to join the others. I happily took my place among my other Literary Arts peers like Joy Kogawa, Roy Kiyooka, Gerry Shikatani, Terry Watada and the late, David Fujino. When I received my copy of the directory, I flipped through the pages, found my name, found the names of other people in my discipline, and felt both affirmed in my vocation and part of a community. Then I put the directory on my shelf and didn’t look at it again for years.

Meanwhile, I struggled as a writer. I struggled in two ways because I wanted to be genuine and authentic to who I was as a Japanese Canadian and as a writer. There is the person, and then there is the medium by which the person communicates herself. But who was this Japanese Canadian person? How could this person know who she was unless she expressed it? There is a white space, and then one draws a circle. Where there was nothing once, there is something. Together, the nothing and the something become the art of being.

Aiko Suzuki struggled with her identity, too, in large part in denial of it, until about 1987 at the time of the Redress movement which aimed to educate Canadians about what happened to Japanese Canadians during the war and seek redress from the Canadian government for its wartime actions against its own citizens. It was a vulnerable time – and those who sought to stay invisible – now became visible, including the artists. In the 1987 Shikata ga nai Exhibit catalogue (organized by Hamilton Artists Inc. and curated by Bryce Kanbara.) Aiko Suzuki said this,

Only recently have I dealt with the genetic reality of being a Japanese-Canadian female artist. For too many years I have been disappointed in the condescending attitude of “Boys’ Clubs”; for too many years I have responded with “…if the name wasn’t’ Suzuki would you still call it ‘oriental’?” Now I accept those sometimes, subtle , sometimes overt “feminine” and “oriental” qualities as fundamental and natural to my vocabulary as an artist..

Her comments touch on the nature of tokenism for it is one thing to produce the art of your being, and quite another to have it categorized. Artists tend to eschew labels – they want, above all, to be seen as human – but once the art goes out into the world, a vocabulary must be generated to describe it and the artist who created it.

Poet and visual artist Roy Kiyooka was a great one for coming up with words, and he coined it nicely when he called himself at the time ‘a real nip-loner prowling the mainstream of canart-o!’ Of course, like Aiko, he asked the question ‘does our notion/s of success colour us more than say ethnic lip-service?’ In other words, was being Japanese Canadian something ‘fashionable’ enough to exploit as a means of getting attention for one’s work? It seemed like a directory with the name ‘Japanese Canadian’ in it was intended for just that kind of exploitation in a world ‘hot’ for ‘multiculturalism.’

I prefer not to see it that way. For me, the word that rung true in Kiyooka’s summation of things was ‘nip-loner.’ It was lonely being an artist working in disciplines often without other Japanese Canadians present drawing from the same histories or influences. And although solitude may be what is necessary to create, a community is what is required for the creation to be received and appreciated.

Aiko’s epiphany and her innate ability to ‘forge connections’ was what enabled her to gather together a community of artists disparate in disciplines and aesthetic sensibility to create the directory. Once the idea was breathed out, people came out to help execute the vision. The Japanese Canadian community was excited about this directory. They saw it as a necessary networking tool whose time had come. Ethnocentric, it may well have been, and even if it did seem like ‘herding cats’ under the moniker of ‘Japanese Canadian artist,’ people rallied around the idea of it. As Bryce Kanbara said in his introduction to the directory:

There is a need for a renewal of community to give context and meaning to individual striving. Across Canada, there are flashes of artistic expression that light up our connections with heritage, identity, community … The point, then, is to view communality as an alliance of resources, a salutary atmosphere of creative action.

People were inspired by the directory, and a further project grew out of it, the compiling of a data base and resource guide of Japanese Canadian materials. Whereas the directory contained artists, the resource guide (which is attached to this website as view-on tab,) contained materials about Japanese Canadians that explored their identity and documented their experience – much of which was written by or produced by artists in the directory.

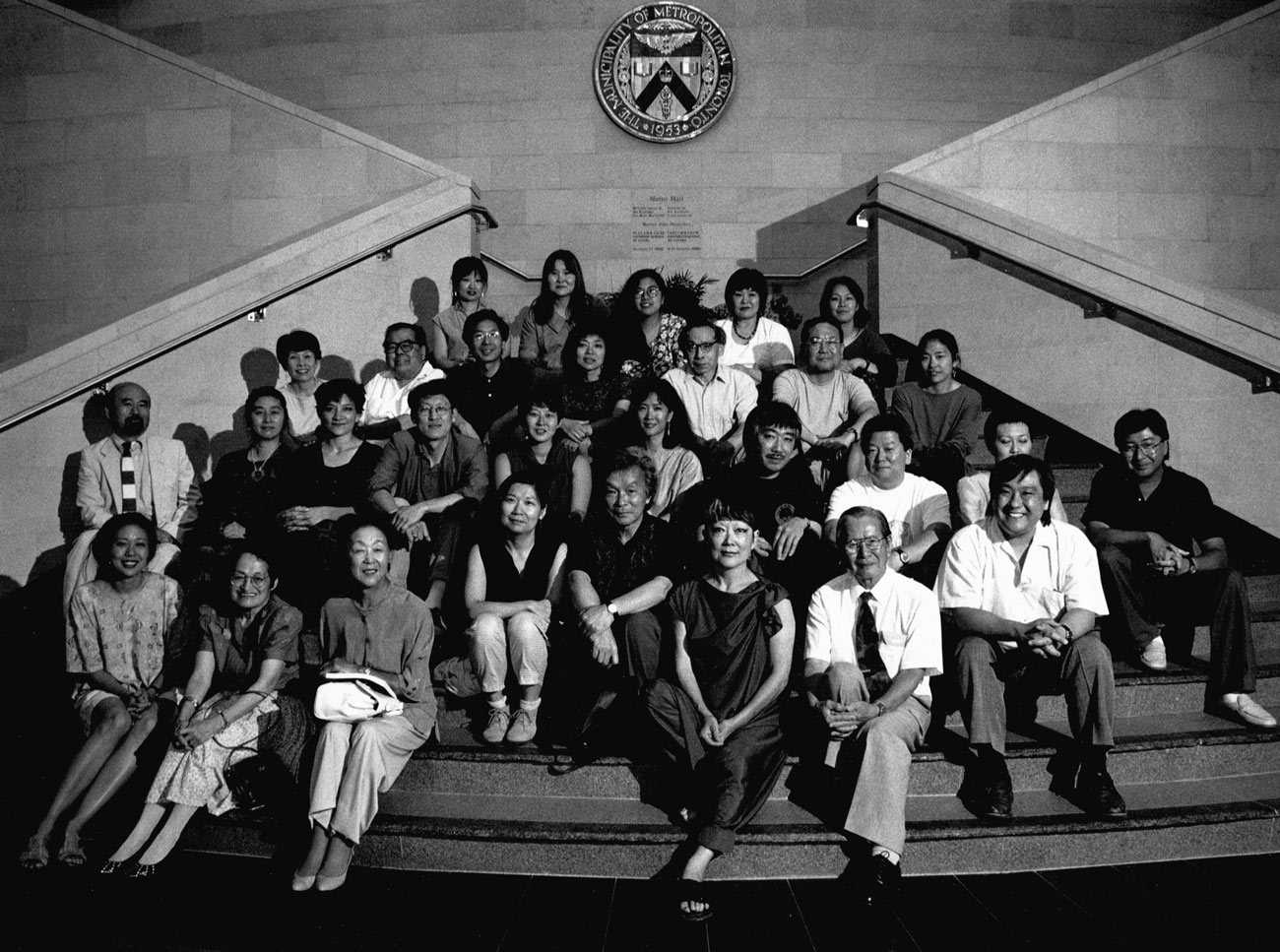

On June 16, 1994, over one hundred people turned out for the launch of the directory at Metro Hall in Toronto. A notable photograph was taken of the artists. It was a great moment of solidarity and celebration.

And then as it does, time marched on.

Flash forward to 2017. It is Canada’s 150th anniversary, and the 75th anniversary of Japanese Canadian internment. A few of those artists who appeared in the photo of 1994 or were in the directory are gone, including Aiko Suzuki who died in 2005 and more recently David Fujino who died in the spring of 2017; many more are grey-haired with years of working in their chosen disciplines, a plethora of exhibits, books, buildings, installations, concerts, albums, films under their belts. All this occurred while a new and powerful tool has become the medium of dissemination for a whole generation of young people – the internet. Communication and connection is instant. But as wonderful as the internet is, it is also shallow. There are many things it does not contain; there are absences.

When it was decided by a group of committed Japanese Canadians from the National Association of Japanese Canadians, the Powell Street Festival Society and the Toronto Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre to revisit the directory and create an online iteration of it, the intent was two-fold. The digital iteration would look backwards, acknowledging the artists of the past who were in that directory as well as others who weren’t but for whom there was some documented evidence of activity who should have a digital presence – a footprint, as it were – for a generation who would look first to the digital before digging deeper into books and archives. At the same time, the online directory would also do what it did for the generation before – provide a networking hub for current practicing and emerging artists in search of community as well as providing them with inspiration from the past efforts of others. What Aiko Suzuki’s original directory did was create community around the idea of Japanese Canadian artistry. And now the digital iteration of this directory aims to remember that artistry while still exploring the idea of it for a new generation. In essence, the old who remember have gathered again this time to help the young discover. And the same funding bodies who believed in this vision almost twenty five years ago and supported it then, feel the same urge to support it now. Hence this iteration of the directory in a new digital form. For posterity, yes, and for the future, too.

- Sally Ito

- June 2017